Guest contributor: Philip Webb

My career as a children’s book illustrator began in the 1970’s and in that time I have changed and developed my style of work. For years I have used the traditional approach using pen or pencil line on watercolour paper. Line has been an important component in my work, and I have always admired the work of Ardizionne and E.H. Shepherd. The line is loose but contains a lot of detail which is left for the imagination to interpret. I also admire the work of John Burningham and Quentin Blake to mention just a few. To the line I have added layers of watercolour paint, starting with the shadows and half tones. The whole process is very tactile and enjoyable. Pencil roughs and final art have been sent to the publisher by overnight courier.

More recently pencil roughs are emailed and large files of finished art scanned to disc or sent via the internet on dropbox- a much more convenient system! The requirement for digital artwork has meant a big learning curve for me. I still hand draw the line and scan this into photoshop on the computer. All colour work is blocked in, carefully following the CMYK colour charts. Shadows and halftones follow this and the process finishes with highlights and texture. Sometimes I will add a watercolour paper texture. Another process I use is a base flat colour layered over the line work which I then slowly paint in to. I learnt this from underpainting in oils on canvas. It gives a bit more spontaneous texture and a slight painterly look. While making changes digitally is much easier, I don’t find working digitally otherwise is any faster than traditional work. Colour and tone is a lot stronger but I am unable to catch the tactile and subtle features of painting on paper, which I would prefer for some of my books. I am sure more experienced and younger digital illustrators would be able to do this.

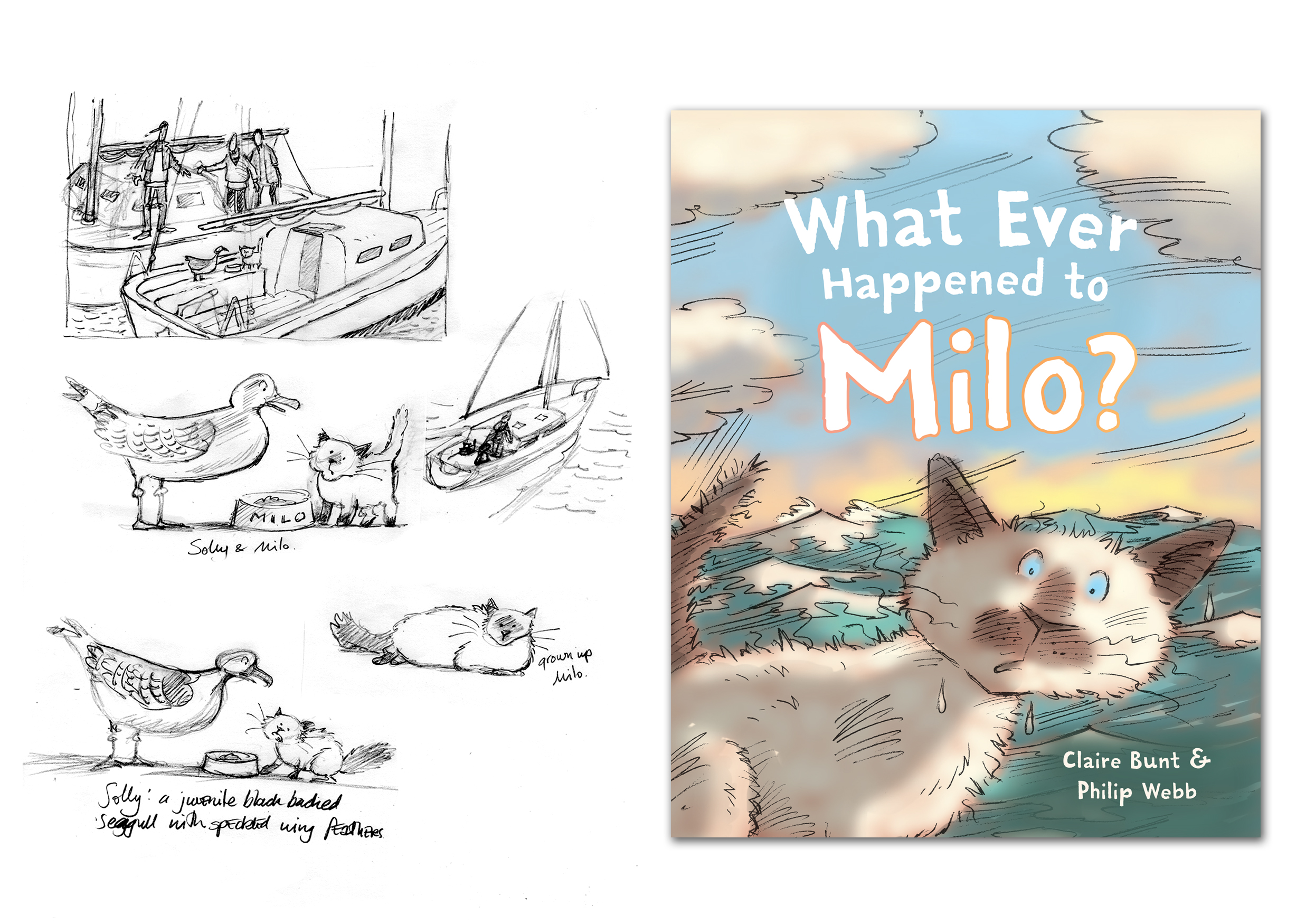

Regardless of how the final artwork is rendered however, I personally think the most important and time consuming stage is at the pencil rough stage. Don’t throw your better pencil roughs away as they can sometimes be better than the final art! I think other illustrators would agree.

For me the success of the final illustration comes down to how good the original drawing and composition is. I look back on some of my earlier work with embarrassment, the only consolation being that my drawing style continues to change for the better!

Philip Webb, Illustrator

Initial pencil sketches and final cover of “What Ever Happened to Milo?”. Written by Claire Bunt, illustrated by Philip Webb